And, I suppose, an update on me. I’m still here! And just fine, though I’ve been really busy the last few weeks. I’ve been working five days a week at Innis Point Bird Observatory since the end of April, which amounts to the same number of hours as if I were working a typical 9-to-5, except I’m getting up before 3:30am every morning to do it and then I spend seven hours largely on my feet. Needless to say, by the time I get home I don’t have a lot of energy for things, and what energy I do have has to be judiciously distributed among my main priorities. Lately one of said priorities has been the moth guide; since I know all of you are eagerly looking forward to getting your hands on a copy the moment it’s available, David and I have been working the last couple of weeks for its prompt return to the publisher to ensure no delays in its publication.

I’ve found being involved behind-the-scenes on this project incredibly enlightening as to what goes on in the production of all those volumes resting on my bookshelves. I’m not sure I’d ever really given much thought to how they came to be, or if I did it was simply along the lines of author writes book, publisher publishes book. But there many more steps, and a lot more people involved, than that. The author(s) writes the book, sure, and submits it to their editor. But their involvement doesn’t end with the manuscript’s submission. The editor goes over the whole thing and sends it back for correction/revision. Then a copyeditor goes over the entire book again. That’s the stage we’re currently at.

The copyeditor is a godsend. Their job is to make sure the author doesn’t look like an idiot. They go through the manuscript with a metaphorical fine-toothed comb, cross-checking the details to make sure no mistakes or dumb goofs have slipped in. And believe me, when you’re working with something of this complexity, mistakes will slip in. It may be something as simple as forgetting to write in the host plants for one species. It may be misspelling the name in one spot. Realizing you left out an oft-used technical term from the glossary. Omitting the male/female plate labels for a species. Inconsistencies in vocabulary, calling the tree a tamarack in this account but eastern larch in this other; or calling a species a leafroller here but a leaffolder there. (Works of fiction also have copyeditors, incidentally; they’re looking for inconsistencies in plot or scene or other loose threads.) I must admit, I had gone through the manuscript before submitting it last fall, so I was a little dismayed be the red pencil all over it when the 4.5 inch stack of paper was returned to me. Dismayed, but very grateful.

I thought it might take me six or eight hours to work through all the corrections, and figured I could get it done in one full Saturday of work. But, as it seems I do at every stage so far, I severely underestimated how long it would take. (I honestly have a whole new respect for the authors of the field guides on my shelves. It might not be complicated, but it’s a helluva lot of work.) Some 30 hours later I finally bundled up the last of the papers into the box they were sent in and took them back to the post office. Needless to say, this has taken up most of my spare waking hours for the last couple of weeks, and I didn’t have many to spare to begin with.

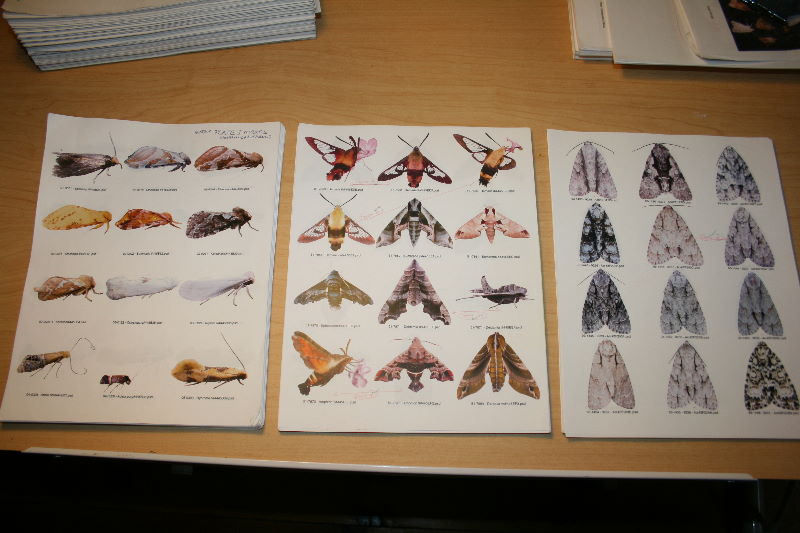

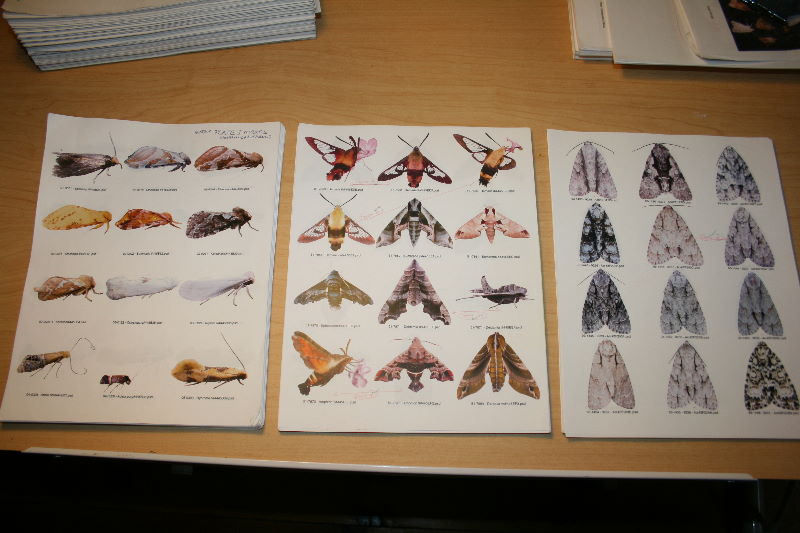

Still, it was pretty neat to see the book moving forward. The part that really made it seem real to me, like it was actually going to become a bunch of pages bound inside a cover, were the images for the plates. All laid out together in rows, the moths clipped out and on a white background, it was already starting to feel like a guide. Once the publisher receives my box next week the materials go on to composition. Some poor person will spend the next several weeks taking all of our bits and pieces from their many sources and bringing them together in one spot, for species after species. We’ll have an opportunity to look over the first couple that get done, to ensure that it all looks correct before the compositor does four hundred of them. Then once the compositor is done, we’ll have another round of proofing, this time going over the laid-out plates. It’ll really be starting to look like a book then.

Here are all the different components of the book, sent to us for our review of the copyeditor’s mark-up. From left to right: the graphics illustrating the flight period for each species, the range maps for each species, the plate images, the endplate (inside-cover) silhouettes, the terminology diagrams for the introduction and the endplates, the photos for the introduction, and then the full manuscript, including the intro and end materials and the species accounts themselves. Each species has components in five spots (flight period, map, image, species account, checklist entry) and trying to keep track of everything can get a little confusing!

Now that that’s been mailed back, I’m hoping to get myself back into the habit of posting every two or three days here. I’ve got a huge backlog of photos that need clearing out, and now that summer’s arrived there’ll be more coming in every time I go out hiking. The posts might be a little shorter, but shorter is better than not at all. ;)