One of the hardest things to photograph is a track or print in the snow. All the same colour, with virtually no contrast. But I did my best with this one, tweaking it a bit in Photoshop to help bring out the details.

Dan found this near the tractor shed while out with Raven a couple of days ago, before we got flooded with rain. The area is at the edge of the fields that surround our house, in a narrow strip of deciduous woods that separates our property from that of our neighbours.

It was obviously made by a bird, most likely swooping down to the ground to pounce on something, although I’ve seen marks like this made by startled grouse that pop up from the ground to take off. There weren’t any tracks leading up to it, though, and it wasn’t close enough to cover for it to have been a grouse asleep in a snow hollow.

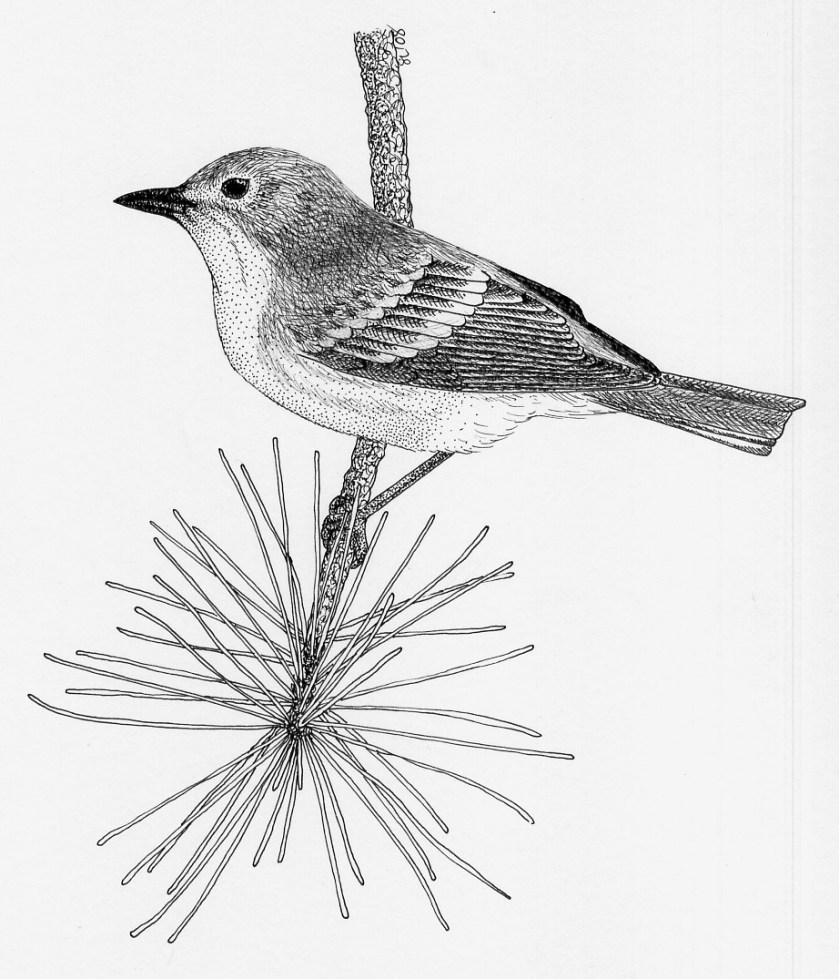

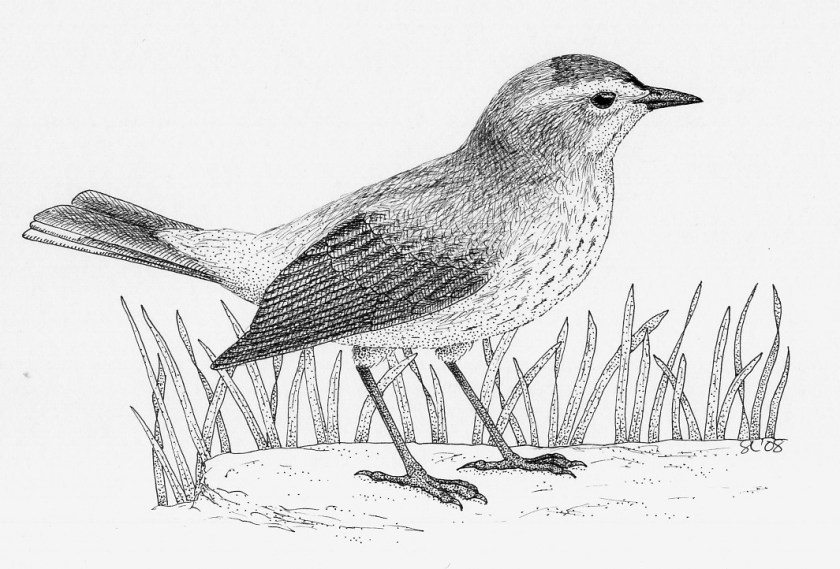

The size of it (see next photo) and these circumstances led Dan and I to believe this print was made by a Northern Saw-whet Owl. These little owls are chunky birds, their bodies roughly the length and breadth of your flat palm. They’ve got relatively stubby wings, short and broad. And they typically forage from a low perch, pouncing on prey that’s traveling on or underneath the snow.

Lending strength to our hypothesis is the fact that on a couple of nights just recently we’ve heard a saw-whet calling from the woods bordering our property. While it’s possible that the calling individual might be one that’s passing through, there are patches of ideal habitat on the neighbouring land, and saw-whets were recorded breeding in the region during the most recent bird atlas. Saw-whets, like most owls, are also early breeders, though not quite as early as some of our local species, such as the Great Horned. Saw-whets would be starting to court now, and find and establish nest sites. Eggs will likely be laid in three to four weeks.

Though these little owls will take a variety of small vertebrates as prey, their primary food item is voles. We have no shortage of voles around here, which like the wide meadow habitat. When food is plentiful, saw-whets may catch more than they need and cache some instead of eating it immediately. When they’re ready to return to it, they thaw it out by holding it in their feet on a branch and sitting on it, tucking it into their belly feathers like they would do with an egg they were brooding.

A pretty neat find! We’ll keep our ears open in the evenings to see if we can determine where the bird has set up a territory, if it is indeed breeding here, and then in a few weeks try to locate its nest cavity.